While the rest of the world struggled to shift work and school online, Estonia was already there

In “The Hidden World of IT Legacy Systems,” I describe how the Covid-19 pandemic spotlighted the problems legacy IT systems pose for companies, and how they especially affect governments. A recent Bloomberg News story that discussed how government legacy IT systems in Japan are holding back that country’s economic recovery further illustrates the magnitude of the problem.

Japanese economist Yukio Noguchi is quoted in the story as warning that the country is “behind the world by at least 20 years” in administrative technology. The poor shape of Japan’s governmental IT hinders the country’s global competitiveness by restraining private sector technological advances.

This helps explain why, despite being the world’s third-largest economy, Japan is now ranked only 23rd out of 63 countries when it comes to digital competitiveness as measured by the IMD World Competitiveness Center, a Swiss business school. In addition, the frayed IT infrastructure has diminished the potential benefits from the government’s $2.2 trillion pandemic fiscal stimulus, the Bloomberg story states.

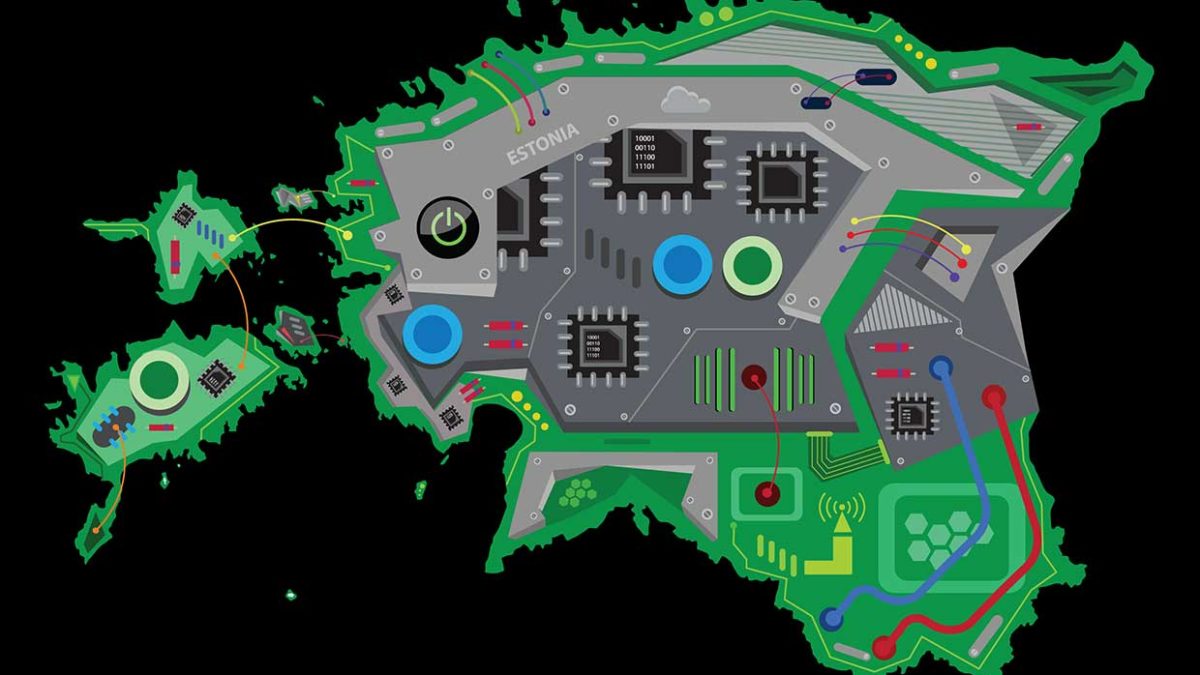

One the other hand, Estonia’s IT systems that have weathered the pandemic well. According to an article from the World Economic Forum, during the country’s pandemic lock-down, the country’s online government services continued to be readily available. Further, its schools experienced little difficulty supporting digital learning, remote working seems to have been a non-issue, and its health information systems were able to be quickly reconfigured to provide information about newly diagnosed Covid-19 cases in near real-time; contact tracers were able to be updated with new case information five times a day, for example.

Why has Estonia’s IT systems been able to handle the pandemic so well? In the words of David Eaves from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, by being both “lucky and good.” Eaves says Estonia was “lucky” because, after the Baltic country won back its independence from Russia in August 1991 and the last Russian troops left in 1994, the country of 1.3 million people found itself desperately poor. The Russians, Eaves notes, “took everything,” leaving essentially a clean-slate IT and telecommunications environment.

Eaves states Estonia was “good” in that its political leadership was savvy enough to recognize how important modern technology was not only to its future economy but its political stability and independence. Eaves said being poor meant that the country’s leadership could not “afford to make bad decisions,” like richer countries. Estonia began by modernizing its telecommunications infrastructure—mobile first because it was easiest and cheapest—followed by a fiber-optic backbone, and then beginning in 2001, public Wi-Fi areas, which were set up across the country.

The Estonian government realized early on that world-class communications, along with universal access to the Internet, were key to quickly modernizing industry as well as government. Estonia embarked on a program to digitalize government operations and planned the extensive use of the Internet to allow its citizens to communicate and interact with the government. Eaves states that Estonia’s political leadership also understood that to do so successfully required the creation of the necessary legal infrastructure. For example, this meant ensuring the protection of individual privacy, safeguarding personal information and providing total transparency regarding on how personal data would be used. Without these, Estonians would not trust a totally wired government or society, especially after its unpleasant experience of being part of the Soviet Union.

Estonia also wanted to avoid being encumbered with old technologies to reduce IT system maintenance costs, so it decided to adopt an eliminate “legacy IT” principle. In other words, for systems in the public sector, the government decreed that, “IT solutions of material importance must never be older than 13-years-old.” Once a system reaches ten-years-old, it must be reviewed and then replaced before it becomes a teenager. While the 13-year period seems arbitrary, it serves the purpose of a forcing function to ensure existing systems don’t fall into the prevailing twilight world of technology maintenance.

Estonia proudly proclaims that along with 99 percent of its public services being online 24/7, “E-services are only impossible for marriages, divorces and real-estate transactions—you still have to get out of the house for those.” Everything else, from voting to filing taxes, can easily be done online securely and quickly.

This is possible because since 2007, there has been an information “once only” policy, where the government cannot ask citizens to re-enter the same information twice. If your personal information was collected by the census bureau, the hospital will not ask for the same information again, for example. This policy meant different government ministries had to figure out how to share and protect citizen information, which had an added benefit of making their operations very efficient. Estonia’s online tax system is reported to allow people to file their taxes in as little as three minutes.

Scaling up Estonia’s e-Governance ecosystem [PDF] to larger countries might not be easy. However, there is still much to be learned about what an e-government approach can achieve, and which IT legacy modernization strategies might be quickly implemented, Eaves argues.

Yet, even in Estonia, there are a few dark clouds forming in the distance over its IT systems. The government’s Chief Information Officer Siim Sikkut has repeatedly warned that while there has been funding available to build new online capabilities, the country’s IT infrastructure has been chronically under-funded for several years. Sikkut argues that it may be time to start shifting the balance of funding away from new IT initiatives to supporting and replacing existing systems. A September 2019 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development report indicates that Estonia needs to spend approximately 1.5% of the state budget on its digitalization efforts, but is only currently spending around 1.1% to 1.3%.

Finding more IT modernization funding to make up the shortfall may not be easy, given the pandemic’s economic impacts on Estonia and other competing government e-governance objectives. Given its seeming e-governance prowess, Estonia is surprisingly only ranked 29th by the IMD in global competitiveness, a position the government wants to rectify, which will require even more funding of new IT initiatives.

It will be interesting to see over the long run whether Estonia will be able to find the funding for both new IT initiatives and IT modernizations, or if it will choose to fund the former over the latter, and end up stumbling into the legacy IT system trap like so many other countries have.